tikkun olam & climate eschatology (there is no such thing as the end of the world)

I would like to start by quoting at length from David Graeber's book on debt.

On the one hand, (capitalism’s) exponents do often feel obliged to present it as eternal, because they insist that is it is the only possible viable economic system: one that, as they still sometimes like to say, "has existed for five thousand years and will exist for five thousand more." On the other hand, it does seem that the moment a significant portion of the population begins to actually believe this, and particularly, starts treating credit institutions as if they really will be around forever, everything goes haywire. Note here how it was the most sober, cautious, responsible capitalist regimes—the seventeenth-century Dutch Republic, the eighteenth-century British Commonwealth—the ones most careful about managing their public debt—that saw the most bizarre explosions of speculative frenzy, the tulip manias and South Sea bubbles. (...)

Almost none of the great theorists of capitalism, from anywhere on the political spectrum, from Marx to Weber, to Schumpeter, to von Mises, felt that capitalism was likely to be around for more than another generation or two at the most. (...)

One could go further: the moment that the fear of imminent social revolution no longer seemed plausible, by the end of World War II, we were immediately presented with the specter of nuclear holocaust. Then, when that no longer seemed plausible, we discovered global warming. This is not to say that these threats were not, and are not, real. Yet it does seem strange that capitalism feels the constant need to imagine, or to actually manufacture, the means of its own imminent extinction. (...)

Perhaps the reason is because what was true in 1710 is still true. Presented with the prospect of its own eternity, capitalism—or anyway, financial capitalism—simply explodes. Because if there's no end to it, there's absolutely no reason not to generate credit—that is, future money—infinitely. Recent events would certainly seem to confirm this. The period leading up to 2008 was one in which many began to believe that capitalism really was going to be around forever; at the very least, no one seemed any longer to be able to imagine an alternative. The immediate effect was a series of increasingly reckless bubbles that brought the whole apparatus crashing down.

(David Graeber, Debt: The First 500 Years, 2011, 357-360.)

In other words, the cliché that 'it is easier to imagine the end of the world than to imagine the end of capitalism' doesn't go far enough. Because capitalism is fundamentally unsustainable on so many levels, it is necessary to believe that the end of the world is coming in order to keep buying into it.

The framework I encounter most often to understand the climate crisis and its accompanying social breakdowns is Protestant apocalypse theology. In this theology, things get steadily worse until they are as bad as I, the speaker, can possibly imagine, and then there is a final climax of salvation, either in the form of a literal Christian Judgement Day, or a secularized version of mass death by nuclear holocaust, zombie plague, etc. Or there is a clean break, after which we live in the 'post-apocalypse,' a dark edenic state of primitive survivalism. I'm going to call this set of ideas and assumptions Apocalypse Ideology.

Apocalypse Ideology occludes reality in many ways. First of all, the binary of before-times/after-times makes us feel that, if the world around us doesn't look like Max Max: Fury Road, everything must be essentially all right. Second, the conscious or unconscious idea that we are on an inevitable march to a final End Time is pacifying. Have you ever tried to bring up climate change during small talk about the weather? Say, when it's in the 50s Fahrenheit in Chicago in January? The reflexive response you often hear is something like 'we're all gonna die!' or 'soon all of this will be underwater' or 'we live in the bad timeline' or 'the end times are coming.' These are self-soothing, pacifying responses; they assimilate information about the breakdown of natural systems into a narrative about history as having a beginning, middle and end. To return to Graeber, if everything is about to come to an end, then we might as well keep 'borrowing' time from the future. When the bank of reality goes out of business, we won't ever have to pay back our debts.

I understand that real Christian eschatology is infinitely complex, and is ultimately pointed toward the direction of redeeming the world from a state of fallenness into a state of grace through divine justice. It's also not fully possible to disentangle Christian and Jewish eschatology, as is true for other branches of theology as well. (See Daniel Boyarin, Border Lines: The Partition of Judaeo-Christianity.) I'm not really interested in getting into the weeds about this. What I want to suggest is that a turn to Jewish messianic eschatology can help us out of the freeze defense mechanism that many of us are stuck in.

I want to turn now to the eschatology of tikkun olam. If you aren't familiar with how tikkun olam has migrated from a rabbinic principle to a kabbalistic to a social justice one, this article is a good introduction to these concepts. To summarize briefly here, tikkun olam:

- appears first in the Aleinu prayer, which is first attested in the 3rd Century CE but might be older. In this text, the line לְתַקֵּן עוֹלָם בְּמַלְכוּת שַׁדַּי ('to fix the world as the Kingdom of Shaddai') refers to the establishment of Hashem's universal kingdom in the coming messianic age.

- is taken up in early Midrash and in the Mishnah, where it refers to a legal principle of 'keeping the peace' or 'maintaining the integrity of social relations.' Where following a law too nicely would create discord and social fracturing, tikkun olam is cited to justify exceptions.

- is expanded and metaphorized in the 16th century by Rabbi Isaac Luria, the father of Lurianic Kabbalah. The story that Luria tells is that the world was made when G-d contracted a small part of G-dself to make room for Other Stuff. G-d then brought Divine Essence into the world in Vessels, but the Divine Essence was too much for the Vessels to hold, and they Broke. This Breaking of the Vessels scattered G-d's Essence throughout the world. The task of humankind is to fix the world by gathering the sparks of Divine Essence, which we do by following the Torah and the Mitzvahs. Each Mitzvah puts the world back together a little bit (tikkun olam), and each bad act breaks it a little bit. When all of the world is put back together, Moshiach will come.

- is then taken up starting in the 1950s by the Reform Movement and American Jews engaged in social justice work as a theological basis for Jewish participation in social movements.

By this point in history, tikkun olam has settled into the realm of cliché. Certainly, this one principle is not enough to hang our entire worldview on. But I wonder if reintegrating tikkun olam with its origins as a formula for the end of the world can help it feel more meaningful again?

The Christian book of Apokálypsis/Revelation, from whence Apocalypse Ideology springs, takes its writing style from the Prophets. But the Prophets were writing about specific historical events: the fall of the first Temple, the Babylonian exile and captivity. This event, which we commemorate on Tisha B'Av, becomes the blueprint for understanding each successive catastrophe.

What Luria's cosmology of universal brokenness does is it metaphorizes this Jewish experience of History, in which the world falls apart and then is rebuilt again and again. Or, as Walter Benjamin put it:

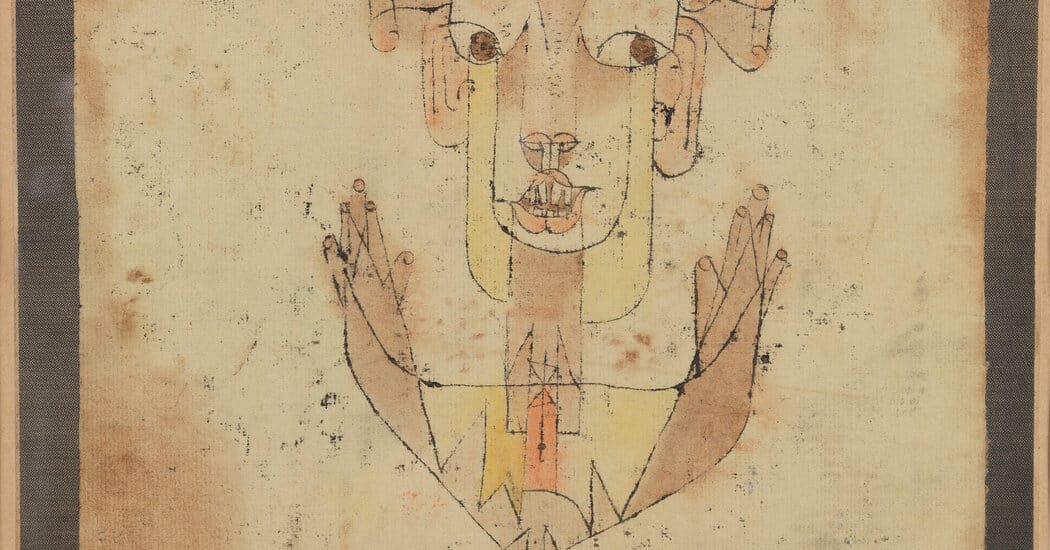

A Klee painting named Angelus Novus shows an angel looking as though he is about to move away from something he is fixedly contemplating. His eyes are staring, his mouth is open, his wings are spread. This is how one pictures the angel of history. His face is turned toward the past. Where we perceive a chain of events, he sees one single catastrophe which keeps piling wreckage upon wreckage and hurls it in front of his feet. The angel would like to stay, awaken the dead, and make whole what has been smashed. But a storm is blowing from Paradise; it has got caught in his wings with such violence that the angel can no longer close them. The storm irresistibly propels him into the future to which his back is turned, while the pile of debris before him grows skyward. This storm is what we call progress.

Tikkun olam is an eschatology that runs in the opposite direction from that of Apocalypse. The end of the world has already happened; the world is shattered from the beginning. Our job is to pick up the pieces.

Again, let's think about how Apocalypse Ideology is part of capitalism. If the world is coming to an end, then we aren't responsible for how the world looks in a thousand or a hundred years, because 'everyone will be dead by then anyway'; or 'the world will be so terrible by then that our actions don't make enough of a difference'; or, as a last ditch, 'I'm not going bring kids into this messed-up world, so it's not my responsibility what happens to the descendants of those who do.' It's a self-soothing set of beliefs that, as Graeber shows, allows us to keep borrowing resources from a future we think will never ask us to pay it back.

Tikkun olam means that the power to shape reality is in our hands. That radical agency is why we are bound by a covenant, and why we have a responsibility to honor that covenant, no matter how bad the world gets. But our individual righteous acts don't necessarily lead to our own salvation. Recall the teaching of Rabbi Ḥanina that I discussed in my last post. As human beings, we have free will: G-d does not have the power to compel us to honor the terms of the covenant. On an individual level, we do not receive divine justice for our good or bad deeds. Nor even do we necessarily receive this justice on a communal level--see, for example, the disproportionate impact of climate change on the least-polluting nations in the Global South. But our actions do have real impact on the shape of the world, in ways that are never clear ahead of time.

In non-theistic terms, what this means is that the incomprehensibly complex systems that govern reality do not have the power to make us understand or respect them. The soil doesn't tell us it's been depleted by industrial agriculture except through its observable actions. But even these observable actions (reduced crop yields) don't inherently force us to make a different choice. That's still up to us. We always have the option to honor or dishonor the terms of our reality. Any act of honoring these terms makes the world better; any act of dishonoring them makes the world worse. There is no apocalypse coming to save us: there is only, always, our own capacity to do good and to do harm.

Because I'm trying to make conceptual tools for us to bring back to our movements, here are some sloganized versions of the ideas I'm working with here:

In my next post, I want to go further into the idea of the Covenant as an ethical framework for right-sizing our responsibilities in the face of climate breakdown. Thank you for reading. Be well!